The Great Shark Debate – Are numbers booming?

The Great Shark Debate

There’s no doubt that over the past few years sharks have become a hot topic among the Australian public, with increased sightings and attacks raising questions on their numbers and behaviour. For many across the nation it’s become a touchy and heated debate, with conservation groups doing their best to down play and protect the sharks while others have strong opinions that we have a shark epidemic requiring urgent attention. Like many fishers, I regularly experience negative shark encounters, so it’s easy to dislike these apex predators and form a less than desirable opinion of them.

For well over a year I have been researching and collecting data and facts on this subject because I felt my own experiences weren’t enough to warrant a credible opinion. What I learnt was interesting but somewhat concerning and I will let you make your own decision based on the information I have gathered.

Why are sharks important for our ecosystem?

With sharks considered as the top food chain, they become a “keystone species” which means they have an extremely important job ensuring a correct balance in the ecosystem. Without sharks we would start to see an imbalance between various fish species and other marine life, which can have detrimental flow-on affects. For example, here in Australia a study was completed on two reef systems. One reef had been depleted of sharks due to illegal fishing and the other had a healthy shark population. The one without sharks had a noticeable increase in fish species such as snappers and emperors, and while anglers might be happy to hear this, the situation unfortunately puts extra pressure on the smaller algae and weed eating species eaten by the larger reef fish. These smaller resident reef species have an important role by eating the algae that prevents coral growth and in some cases stops the coral from recovering from natural occurrences such as cyclones and bleaching. Without the coral there is simply no attraction for marine life.

Another great example comes from an area off the US where shark numbers were hugely reduced due to overfishing. This saw a huge population growth of cow-nose rays, which were the staple diet for many shark species. As the cow-nose rays population grew the number of the scallops they fed on reduced drastically to the point where the commercial shellfish fish industry completely collapsed. This is a fine example of how an imbalance within the ecosystem can have negative flow on affects. I feel this highlights the fact that sharks play a key role in the ecosystem.

Is there a shark population issue?

Is there an imbalance with Shark numbers in our ecosystem? This is the question that divides line fishers, spearfishers and some of the general public from conservationists, scientists and field specialists. There’s no doubt shark issues often create a large social media response, which in turn highlights the subject more than ever and attracts high level media attention. Clearly this can give the impression that we have a problem far greater than what it actually is, so we need to resort to facts to ensure all this attention is justified.

At least all sides can agree that we are indeed seeing an increase in shark attacks all over Australia, with data showing that attack numbers increased by 50 percent between 1995 and 2005 and a further 150 per cent between 2005 and 2015. Some experts indicate this increase is due to the growing Australian population and data shows there is an acceptable alignment between shark attack numbers and population growth. Digging deeper, I soon found that this percentage was far worse back in the 1930s, with about 60 attacks per million people compared to 30 attacks per million people in the current era. What was alarming was the fact that the current number of attacks per person is on the increase and at the highest point since the 1930s and ‘40s. Experts suggest this is due to a combination of the population increase, the growth in the popularity of water based activities, people accessing previously isolated coastal areas and the increasing whale population migrating up and down the coastline each year.

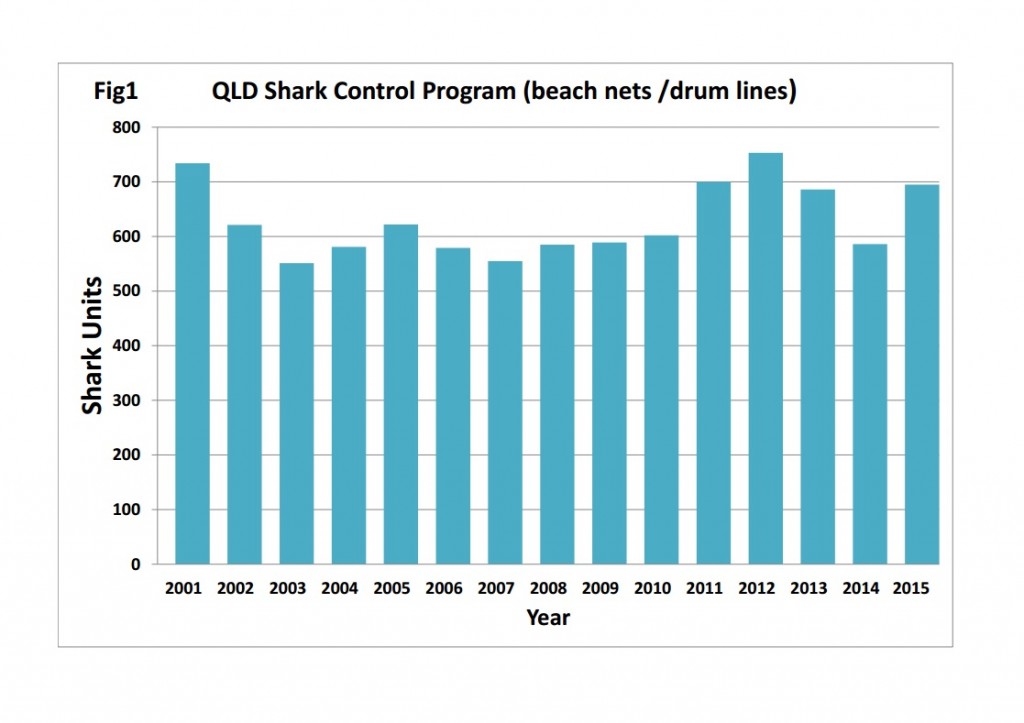

To go one step further, I was highly interested in the data collected from the government funded shark control programs, which have been running along the QLD and NSW coastline since the 1960s. These nets and baited drum lines are located all along the coastline beaches to help protect swimmers from unwanted shark encounters. Unfortunately I could only get data for QLD, but to my surprise there was actually very little increase in the numbers of sharks caught in these programs over the past 15 years. During this time, on average 629 sharks were caught per year, with 686 caught in 2013, 586 in 2014 and 685 in 2015. (See Fig1) Not exactly a noticeable increase one would have thought.

Even though some areas of data show an increase in shark numbers, you would think the conservationists, scientists and specialists in this field are actually right and the rest of us are incorrect with our overpopulated assumptions. If I was only going off those facts and figures then why would anyone think there were issues? I for one don’t hold anything against the researchers who reference the numbers because like any business it really is a numbers game and without them, there’s very little credibility.

So what are fishers, spearfishers and divers complaining about? Are we whinging for nothing? Is social media and media in general making us more aware of this subject and causing us to believe there’s an issue where there isn’t? Well maybe a little but the big answer is NO. The data being gathered relates to shark attacks, nets and drum lines, all of which are close to the beaches. The places where line and spearfishers along with divers are experiencing a shark population boom are on the inshore/offshore reefs, bays and estuaries. We know there’s a huge imbalance within the ecosystem in these areas but these locations are outside the scope of the data and facts being collected and subsequently looked at. The big point here is that beaches are far from the ideal habitat for most shark species, and only when a shark roams or migrates from its ideal habitat does it end up passing close to the beaches. I’m almost certain the main reason they end up close to beaches is because they have followed the migrating bait/fish/whale schools close to the coastline.

Sharks are without a doubt having a population explosion in their ideal environment. Ask any new or old fisher/spearo and they will tell you the situation at its worst ever. I have never seen and had so many issues with sharks and even though I avoid fishing large reef systems, which decreases shark encounters, I’m now seeing shark problems on small isolated reefs that were once trouble free. Visit any large popular reef system and you will be blown away by the sheer number of sharks in these areas. I believe a couple major factors can be blamed for this imbalance: reduced commercial shark fishing and the ability of sharks to learn from human interaction.

Commercial shark fishing has been a huge part of the Australian fishery for an extremely long time. While shark populations in several countries has been reduced and in some cases decimated, Australia leads the way in managing all fishery sectors to ensure species are sustainable for the future. But have we gone too far?

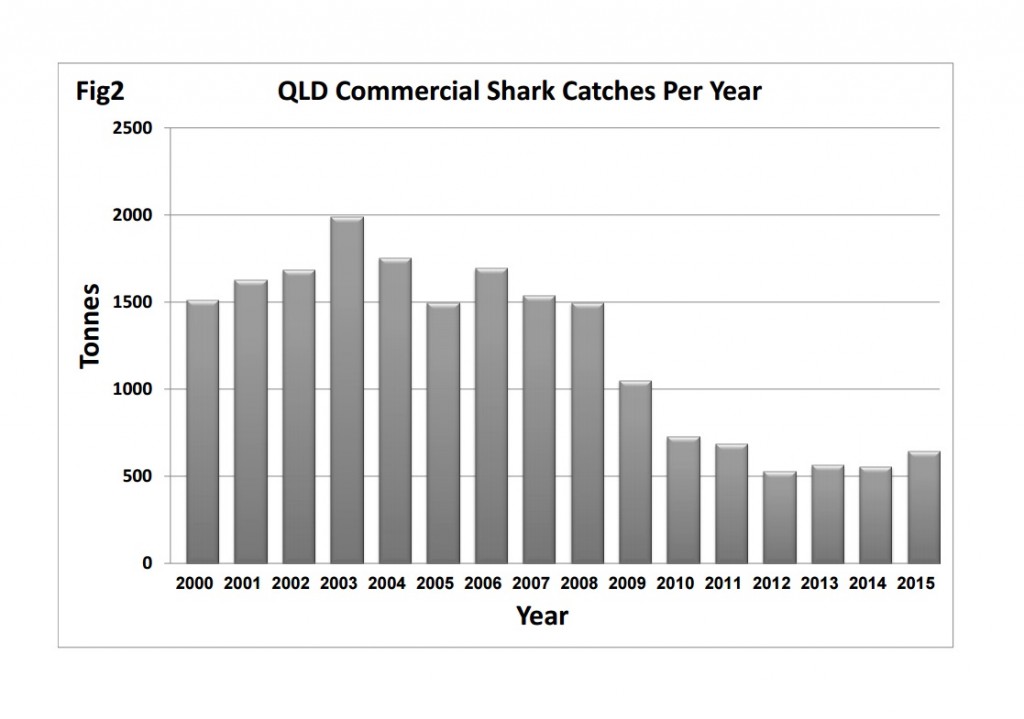

Commercial shark catch data from the mid to late ‘90s indicated an average of 1000 tonnes caught annually in QLD. Between the years of 2000 to 2008 this figure increased to over 1600 tonnes and a change was called for to ensure levels were sustainable. In 2009 a radical change was enforced upon the QLD commercial fishing/netting industry, which also affected recreational fishing. The general public including the fishing and spearing communities, still to this day think commercial shark fishing was stopped due to the 2009 regulation stating sharks over 1.5m in length could not be kept or sold. This however was incorrect and is only applicable to recreational fishers with a set bag limit of one shark per person.

The change put in place for commercial shark fishing was in fact that an “S” symbol fishing licence was introduced and required for sharks to be captured and sold. This licence was only available for those with prior shark catching/selling history and the operators also had to meet particular catch amounts to be eligible. What this has meant is the average number of commercial licences catching/selling sharks has gone from 570 to 330 since the new regulations were implemented in 2009. The average for the past 3 years is now as low as 280 and the average shark catches are now only 580 tonnes per year. So we have gone from catching an average of 1600 tonne of sharks per year to just 580 tonne. (See Fig2) You don’t have to be Albert Einstein to realise this is already causing an imbalance within the ecosystem.

To make matters worse sharks are extremely smart and can quickly learn from their surroundings. To put it simply, sharks are very much creatures of habit. Larger reefs that have an abundance of marine life offer an ideal habitat for sharks, so naturally they gather here in greater numbers. With an increase in their population and a decrease in fish numbers in some areas they begin to work harder and smarter for their food. This is where line and spearfishers become a shark’s best friend. When a fish is hooked or speared it becomes an easy meal for sharks. If this happens time and time again the sharks soon learn that noises from outboards or the sound of a spear gun trigger being pulled are signals that an easy meal is on the cards. Sharks will follow boats, whether reef fishing or trolling, and will simply wait for a fish to be hooked so they can quickly move in and take it. This is the same for trawlers. They throw by catch over the side or even commercial crabbers who throw back undersized crabs while sharks follow them around and wait for an easy feed close by.

Sharks have become so in touch with sounds and habits that some commercial mackerel fishers have 3 or 4 props for their outboards, and when the mackerel are running they swap the props from one day to the next to change the engine’s rev range and noise to avoid sharks becoming accustomed to the sound of their outboards while trolling. This reduces the number of sharked fish and lessens the chance of Sharks learning the sound and thinking it represents an opportunity for an easy meal.

Unfortunately fishers in general are having so much trouble landing fish that we are just wasting them to sharks time and time again, which is really doing us no favours. Spearfishers are also having the same issue but for them it’s at a far greater risk, with the chances of being bitten increasing dramatically.

I can’t see this issue being fixed any time soon because what is experienced on the water differs greatly from what is experienced by scientists and researchers. Studies really need to be conducted in areas ideally suited to sharks, not just on the coastal beaches.

Conservationists would like to think line and spearfishers have very little care for the sustainability of marine species but this is far from the truth. Catch and release methods and the education of fish care are well and truly at an all-time high. We don’t want to see the decimation of shark populations, rather just the correct balance in the ecosystem.

What will it take for experts to take notice? More shark attacks on beaches? Fatal attacks on spearfishers? Only time will tell and until then we will continue to feed and fuel the shark problem.

Regards,

Greg Lamprecht